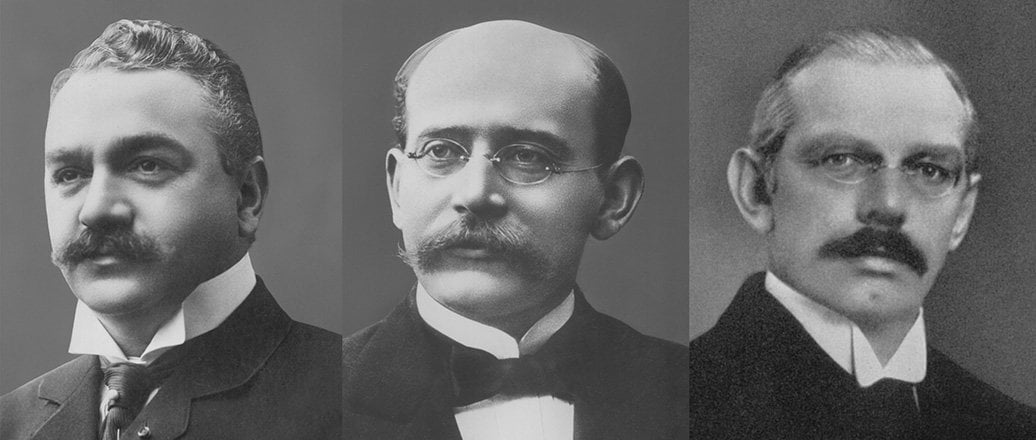

Throughout Hydro’s 100 year history, the roles of each of the company’s three founders and the accolades they deserve have been the subject of much discussion. The debate has focused especially on Eyde and Birkeland. Eyde was of the opinion that his own contribution to taking the arc project from idea to industry was underestimated, and he also played a part in fostering the controversy.

The relationship between Eyde and Birkeland grew more distant over time in comparison with the first definitive years. When Eyde celebrated his 50th birthday in 1916, he said: “Much banded Birkeland and I together in the first years and much divided us in later years…”

Opinions also vary on the significance of Marcus Wallenberg. He has been ranked as equal to and more important than Eyde in bringing about the establishment of the company. This question has been of more academic interest, while the roles of Birkeland and Eyde are a more contentious issue.

During Hydro’s first years following 1905, it was Wallenberg and Eyde who set the tone. They were both highly capable men, but they complemented each other. Eyde’s assertiveness was balanced by Wallenberg’s penchant for thoroughness.

”There was mutual trust between him and me that made it possible for us to accomplish the impossible” Eyde wrote about Wallenberg in his memoirs. They made a dynamic pair.

And the nominees are…

Kristian Birkeland was nominated for the Nobel Prize no less than seven times – both in physics and chemistry. Three times he was nominated together with Sam Eyde.

Eyde wrote in his memoirs that it was a shame Birkeland never won the Nobel Prize, but as far as we know, he also believed that he and Birkeland should be awarded the prize together. This may have been a factor in Birkeland never winning the prize alone. Instead, the German chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch received the prize for developing a new and less energy intensive technology for producing ammonia.

In any case, it was far more important to Hydro that Birkeland, Eyde and Wallenberg combined forces in a way that allowed their visions and ambitions to be realized so early in the 20th century. Reactions varied from enthusiasm and gratitude to disbelief and envy. They had their successes and their disappointments.

Sam Eyde

Sam Eyde grew up in a shipping family in Arendal, Southern Norway, at a time when sailing ships still ruled the seven seas. He must have realized at an early age that his destiny was not to be a merchant mariner. He decided instead to study engineering in Berlin, and he stayed on in Germany for an further 10 years after completing his studies.

Eyde later established himself in Norway as an entrepreneur who took on ever larger projects at an “American tempo”. He had an international approach, but stressed many times that his vision was to develop the young Norwegian nation.

As a captain of industry, Eyde was known for his extraordinary ability to think and work both in terms of present needs and future visions. He was able to work simultaneously on immediate, pressing technical issues, while planning the financing and organization of projects that could only be realized at an uncertain future date.

Eyde had enormous drive and capacity for work, which he applied in so many directions at once that he drew criticism for spreading himself too thin. His social skills were well developed and he used them to the full – with colleagues, as well as in meetings with leaders and workers. His organizational skills were indisputable.

At the same time, he was a vain man and wanted his full share of recognition for the industrialization process he led. His autobiography, which was published just a few months before he died in 1939, can in many ways be interpreted as a statement of defense. Eyde did not want to be forgotten - and has not been either.

Kristian Birkeland (1867-1917):

At the age of 30, Kristian Birkeland was appointed professor of physics at the University of Christiania (now Oslo). But he wasn’t just an academic, as is clearly evident from his work as an inventor. He took out 59 patents - and was annoyed with himself for not taking better care of some of this inventions. One example is the X-ray, which he worked on in 1895.

Birkeland’s wealth of ideas may seem boundless. His patents ranged from electromagnetic cannons and electro-metallurgical melting furnaces, to methods for hardening fats, hearing aids and organic waste treatment. Most did not progress beyond the patent stage. He also worked on a method for utilizing atomic energy.

Kristian Birkeland started his research career as a pure mathematician, before turning to theoretical and experimental physics. He was one of the foremost researchers into astrophysics at the time, and carried out spectacular experiments in the university laboratory, where he reproduced such phenomena as the northern lights and the rings of Saturn. He also conducted several challenging expeditions to broaden knowledge in these areas.

During the development of Norsk Hydro, Birkeland’s involvement was crucial in several phases. He worked hard to ensure that ideas could be applied on an industrial scale and he played an extensive role when Hydro years later needed to replace the furnaces at Notodden with larger units. It was said that Birkeland worked day and night during the period 1903-1907, at the end of which he withdrew his ownership stake in Hydro.

His input in promoting Norway’s industrial development can be seen as a testament to his strong belief in science and its importance to the country’s modernization.

As a person, Birkeland was complex and out of the ordinary; at times he was seen as a visionary. He could be enthusiastic and intense, but he also suffered weak mental health throughout his adult life. He did not take care of himself during his intense working periods, when he often went short of both sleep and food.

The professor of Physics Alv Egeland gave Birkeland the following characterization in a 1994 article: ”Following Birkeland’s life and life work is like an adventure. His intellectual abilities must have been enormous.”

In Norway, Birkeland is a person everyone, in principle, has a relationship to – his face is on the NOK 200 note, which the Norwegian National Bank has issued since 1994.

Marcus Wallenberg (1864-1943):

Marcus Wallenberg was educated as a lawyer and from 1890 worked for Stockholm’s Enskilda Bank. He came from a family engaged for several generations in banking and industrial development in Sweden, Scandinavia and Europe.

Marcus Wallenberg, like the rest of his family, tended to maintain a discreet profile. The simple fact that he served on the Hydro board for 37 years – through good times and bad – says much about his personal qualities.

Since his death, however, he is known at least as much for the part he played in Sweden’s economic development during the first half of the 20th century. His contribution is so undisputed that it may partly explain the apparent peace that prevailed throughout the century between the country’s successive governments and the financial milieu that the Wallenbergs represented.

During the union of Norway and Sweden, from 1814-1905, a substantial economic relationship developed between the two countries. It was evident that Marcus Wallenberg and his half-brother Knut were more interested in nourishing these ties than encouraging the strife that eventually led to the dissolution of the union in 1905. Marcus Wallenberg also pointed out himself that he was extensively involved in developing the company Almänna Svenska Elektriska Aktiebolaget (ASEA) at the time he first met Sam Eyde. And an industry based on the Birkeland-Eyde furnace could also mean orders for ASEA.

Knut Wallenberg gradually became more interested in politics, and became Sweden’s foreign minister in 1914. In 1911, he ceded his position as Enskilda Bank’s managing director to Marcus, who now became more visible and a force to be reckoned with. Marcus was given the task, among other things, to strike a trade agreement with Great Britain. The results revealed him to be a brilliant international negotiator.

New tasks awaited, and he developed a position and reputation as an economic and financial authority. He also had obvious strategic abilities, outstanding language skills and a firm understanding of human nature.

Despite his wide range of activities, Wallenberg never let Hydro take a peripheral place in his working day. It is evident that Hydro accrued significant value due to Marcus Wallenberg. He resigned his position as a company board member in 1942 due to illness and died just one year later.

At Hydro’s 50th anniversary in 1955, the editor of the commemorative book, Kristian Anker Olsen, wrote that Marcus Wallenberg’s contribution to Hydro’s beginning and development can simply be summed up thus: “It was fundamental. He’s not just one of three founders; he stands side by side with Eyde and Birkeland in the limelight of history.”

Updated: May 15, 2024