The money ran out before the end of the week, even though people tried to eat as simply as possible. For many industrial workers, news of the revolution in Russia hit home like petrol poured on a fire. Worker councils were set up in Notodden, based on the Russian model. These posed the threat of strikes and radical proletariat action against the government and the business establishment.

No one works well on an empty stomach. The workers were exhausted – and cutting the working day to eight hours was increasingly put forward as a solution. The demand for an eight-hour day was raised in Christiania (now Oslo) in the spring of 1918, and it resonated all the way to Notodden and Rjukan in Telemark.

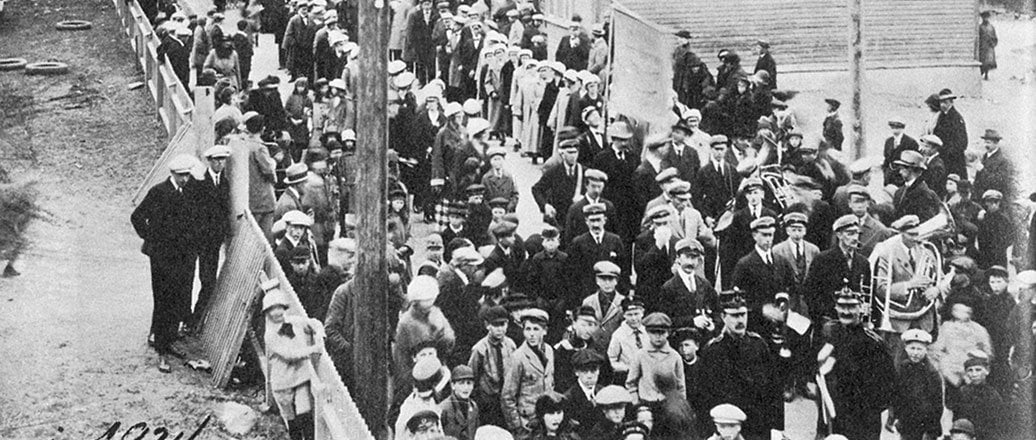

Around 2,000 people marched in the Notodden First of May parade, under the slogan “Yes to the 8-hour day”. The demonstration resulted in a resolution calling for eight hour day legislation.

At later meeting between ten trade union leaders, it decided to wait no longer, and to implement the eight-hour day straight away. Workers at Hydro put words into action. When the factory whistles blew at the end of the next working day, the premises were already empty; everyone had left two hours earlier. It wasn’t long before the example was followed at Rjukan.

The establishment reacted promptly – an order was served to comply with the tariff. The workers summarily ignored it. Meanwhile, the employers’ association started negotiating with a delegation from Notodden and Rjukan. The result was a temporary agreement for a 51-hour work week, in anticipation of a government initiative.

This was presented to the workers for endorsement. Workers at Rjukan agreed, but at Notodden, the compromise was thrown out ”by a large majority at a mass meeting,” according to local newspapers on 22 June.

Two of the trade union leaders also paid a visit to the Prime Minister, Gunnar Knudsen, and demanded his promise that legislation would be passed swiftly. It was passed in the summer of 1919. The ten trade union leaders from Notodden were convicted of inciting a riot and were each ordered to pay fines of NOK 10 (just over one euro at the 2003 exchange rate) – a mild reaction.

The fines were never paid, although the eight-hour day could certainly be considered worth it.

Updated: August 18, 2020